These days, developers are highly likely to be working on a mobile or web application. Python doesn’t have built-in mobile development capabilities, but there are packages you can use to create mobile applications, like Kivy, PyQt, or even Beeware’s Toga library.

These libraries are all major players in the Python mobile space. However, there are some benefits you’ll see if you choose to create mobile applications with Kivy. Not only will your application look the same on all platforms, but you also won’t need to compile your code after every change. What’s more, you’ll be able to use Python’s clear syntax to build your applications.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to:

This tutorial assumes you’re familiar with object-oriented programming. If you’re not, then check out Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) in Python.

Let’s get started!

Free Download: Get a sample chapter from Python Tricks: The Book that shows you Python’s best practices with simple examples you can apply instantly to write more beautiful + Pythonic code.

Kivy was first released in early 2011. This cross-platform Python framework can be deployed to Windows, Mac, Linux, and Raspberry Pi. It supports multitouch events in addition to regular keyboard and mouse inputs. Kivy even supports GPU acceleration of its graphics, since they’re built using OpenGL ES2. The project uses the MIT license, so you can use this library for free and commercial software.

When you create an application with Kivy, you’re creating a Natural User Interface or NUI. The idea behind a Natural User Interface is that the user can easily learn how to use your software with little to no instruction.

Kivy does not attempt to use native controls or widgets. All of its widgets are custom-drawn. This means that Kivy applications will look the same across all platforms. However, it also means that your app’s look and feel will differ from your user’s native applications. This could be a benefit or a drawback, depending on your audience.

Kivy has many dependencies, so it’s recommended that you install it into a Python virtual environment. You can use either Python’s built-in venv library or the virtualenv package. If you’ve never used a Python virtual environment before, then check out Python Virtual Environments: A Primer.

Here’s how you can create a Python virtual environment:

$ python3 -m venv my_kivy_project This will copy your Python 3 executable into a folder called my_kivy_project and add a few other subfolders to that directory.

To use your virtual environment, you need to activate it. On Mac and Linux, you can do that by executing the following while inside the my_kivy_project folder:

$ source bin/activate The command for Windows is similar, but the location of the activate script is inside of the Scripts folder instead of bin .

Now that you have an activated Python virtual environment, you can run pip to install Kivy. On Linux and Mac, you’ll run the following command:

$ python -m pip install kivy On Windows, installation is a bit more complex. Check out the official documentation for how to install Kivy on Windows. (Mac users can also download a dmg file and install Kivy that way.)

If you run into any issues installing Kivy on your platform, then see the Kivy download page for additional instructions.

A widget is an onscreen control that the user will interact with. All graphical user interface toolkits come with a set of widgets. Some common widgets that you may have used include buttons, combo boxes, and tabs. Kivy has many widgets built into its framework.

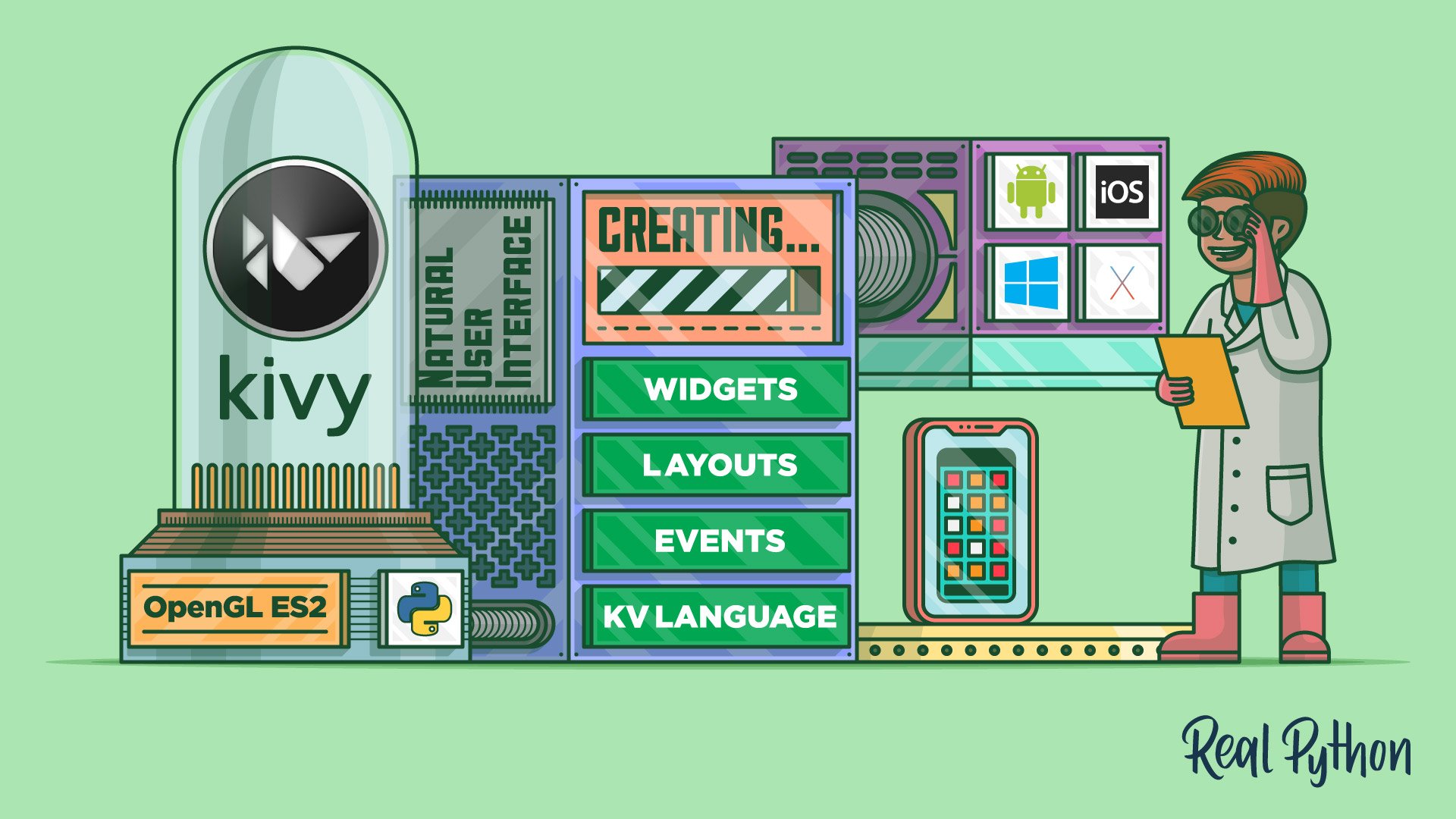

To see how Kivy works, take a look at the following “Hello, World!” application:

from kivy.app import App from kivy.uix.label import Label class MainApp(App): def build(self): label = Label(text='Hello from Kivy', size_hint=(.5, .5), pos_hint='center_x': .5, 'center_y': .5>) return label if __name__ == '__main__': app = MainApp() app.run() Every Kivy application needs to subclass App and override build() . This is where you’ll put your UI code or make calls to other functions that define your UI code. In this case, you create a Label widget and pass in its text , size_hint , and pos_hint . These last two arguments are not required.

size_hint tells Kivy the proportions to use when creating the widget. It takes two numbers:

Both of these numbers can be anywhere between 0 and 1. The default value for both hints is 1. You can also use pos_hint to position the widget. In the code block above, you tell Kivy to center the widget on the x and y axes.

To make the application run, you instantiate your MainApp class and then call run() . When you do so, you should see the following on your screen:

Kivy also outputs a lot of text to stdout :

[INFO ] [Logger ] Record log in /home/mdriscoll/.kivy/logs/kivy_19-06-07_2.txt [INFO ] [Kivy ] v1.11.0 [INFO ] [Kivy ] Installed at "/home/mdriscoll/code/test/lib/python3.6/site-packages/kivy/__init__.py" [INFO ] [Python ] v3.6.7 (default, Oct 22 2018, 11:32:17) [GCC 8.2.0] [INFO ] [Python ] Interpreter at "/home/mdriscoll/code/test/bin/python" [INFO ] [Factory ] 184 symbols loaded [INFO ] [Image ] Providers: img_tex, img_dds, img_sdl2, img_gif (img_pil, img_ffpyplayer ignored) [INFO ] [Text ] Provider: sdl2(['text_pango'] ignored) [INFO ] [Window ] Provider: sdl2(['window_egl_rpi'] ignored) [INFO ] [GL ] Using the "OpenGL" graphics system [INFO ] [GL ] Backend used [INFO ] [GL ] OpenGL version [INFO ] [GL ] OpenGL vendor [INFO ] [GL ] OpenGL renderer [INFO ] [GL ] OpenGL parsed version: 4, 6 [INFO ] [GL ] Shading version [INFO ] [GL ] Texture max size [INFO ] [GL ] Texture max units [INFO ] [Window ] auto add sdl2 input provider [INFO ] [Window ] virtual keyboard not allowed, single mode, not docked [INFO ] [Base ] Start application main loop [INFO ] [GL ] NPOT texture support is available This is useful for debugging your application.

Next, you’ll try adding an Image widget and see how that differs from a Label .

Kivy has a couple of different image-related widgets to choose from. You can use Image to load local images from your hard drive or AsyncImage to load an image from a URL. For this example, you’ll stick with the standard Image class:

from kivy.app import App from kivy.uix.image import Image class MainApp(App): def build(self): img = Image(source='/path/to/real_python.png', size_hint=(1, .5), pos_hint='center_x':.5, 'center_y':.5>) return img if __name__ == '__main__': app = MainApp() app.run() In this code, you import Image from the kivy.uix.image sub-package. The Image class takes a lot of different parameters, but the one that you want to use is source . This tells Kivy which image to load. Here, you pass a fully-qualified path to the image. The rest of the code is the same as what you saw in the previous example.

When you run this code, you’ll see something like the following:

The text from the previous example has been replaced with an image.

Now you’ll learn how to add and arrange multiple widgets in your application.

Each GUI framework that you use has its own method of arranging widgets. For example, in wxPython you’ll use sizers, while in Tkinter you use a layout or geometry manager. With Kivy, you’ll use Layouts. There are several different types of Layouts that you can use. Here are some of the most common ones:

You can search Kivy’s documentation for a full list of available Layouts. You can also look in kivy.uix for the actual source code.

Try out the BoxLayout with this code:

import kivy import random from kivy.app import App from kivy.uix.button import Button from kivy.uix.boxlayout import BoxLayout red = [1,0,0,1] green = [0,1,0,1] blue = [0,0,1,1] purple = [1,0,1,1] class HBoxLayoutExample(App): def build(self): layout = BoxLayout(padding=10) colors = [red, green, blue, purple] for i in range(5): btn = Button(text="Button #%s" % (i+1), background_color=random.choice(colors) ) layout.add_widget(btn) return layout if __name__ == "__main__": app = HBoxLayoutExample() app.run() Here, you import BoxLayout from kivy.uix.boxlayout and instantiate it. Then you create a list of colors, which are themselves lists of Red-Blue-Green (RGB) colors. Finally, you loop over a range of 5, creating a button btn for each iteration. To make things a bit more fun, you set the background_color of the button to a random color. You then add the button to your layout with layout.add_widget(btn) .

When you run this code, you’ll see something like this:

There are 5 randomly-colored buttons, one for each iteration of your for loop.

When you create a layout, there are a few arguments you should know:

Like most GUI toolkits, Kivy is mostly event-based. The framework responds to user keypresses, mouse events, and touch events. Kivy has the concept of a Clock that you can use to schedule function calls for some time in the future.

Kivy also has the concept of Properties , which works with the EventDispatcher . Properties help you do validation checking. They also let you fire events whenever a widget changes its size or position.

Let’s add a button event to your button code from earlier:

from kivy.app import App from kivy.uix.button import Button class MainApp(App): def build(self): button = Button(text='Hello from Kivy', size_hint=(.5, .5), pos_hint='center_x': .5, 'center_y': .5>) button.bind(on_press=self.on_press_button) return button def on_press_button(self, instance): print('You pressed the button!') if __name__ == '__main__': app = MainApp() app.run() In this code, you call button.bind() and link the on_press event to MainApp.on_press_button() . This method implicitly takes in the widget instance , which is the button object itself. Finally, a message will print to stdout whenever the user presses your button.

Kivy also provides a design language called KV that you can use with your Kivy applications. The KV language lets you separate your interface design from the application’s logic. This follows the separation of concerns principle and is part of the Model-View-Controller architectural pattern. You can update the previous example to use the KV language:

from kivy.app import App from kivy.uix.button import Button class ButtonApp(App): def build(self): return Button() def on_press_button(self): print('You pressed the button!') if __name__ == '__main__': app = ButtonApp() app.run() This code might look a bit odd at first glance, as it creates a Button without setting any of its attributes or binding it to any events. What’s happening here is that Kivy will automatically look for a file that has the same name as the class in lowercase, without the App part of the class name.

In this case, the class name is ButtonApp , so Kivy will look for a file named button.kv . If that file exists and is properly formatted, then Kivy will use it to load up the UI. Go ahead and create this file and add the following code:

1: 2 text: 'Press me' 3 size_hint: (.5, .5) 4 pos_hint: 5 on_press: app.on_press_button() Here’s what each line does:

You can set up all of your widgets and layouts inside one or more KV language files. The KV language also supports importing Python modules in KV, creating dynamic classes, and much more. For full details, check out Kivy’s guide to the KV Language.

Now you’re ready to create a real application!

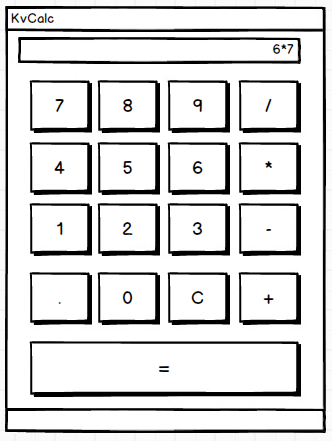

One of the best ways to learn a new skill is by creating something useful. With that in mind, you’ll use Kivy to build a calculator that supports the following operations:

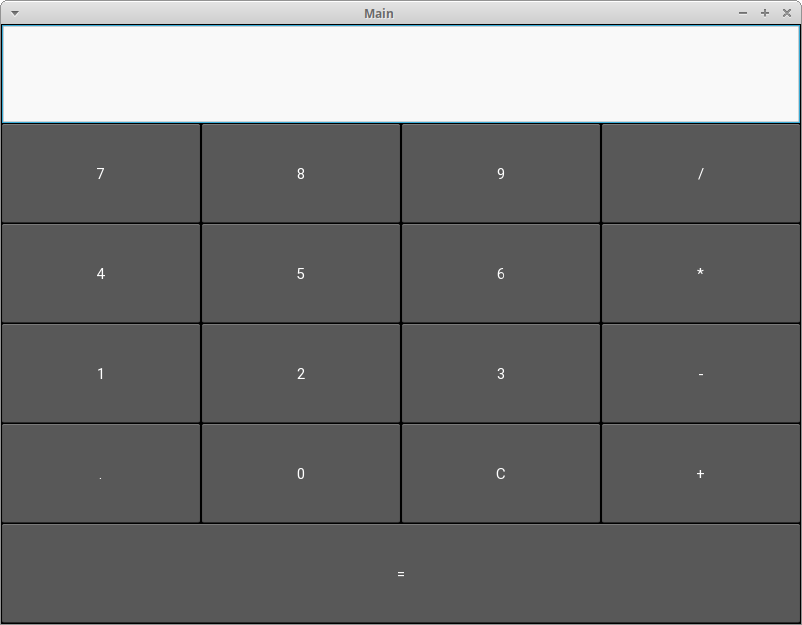

For this application, you’ll need a series of buttons in some kind of layout. You’ll also need a box along the top of your app to display the equations and their results. Here’s a sketch of your calculator:

Now that you have a goal for the UI, you can go ahead and write the code:

1from kivy.app import App 2from kivy.uix.boxlayout import BoxLayout 3from kivy.uix.button import Button 4from kivy.uix.textinput import TextInput 5 6class MainApp(App): 7 def build(self): 8 self.operators = ["/", "*", "+", "-"] 9 self.last_was_operator = None 10 self.last_button = None 11 main_layout = BoxLayout(orientation="vertical") 12 self.solution = TextInput( 13 multiline=False, readonly=True, halign="right", font_size=55 14 ) 15 main_layout.add_widget(self.solution) 16 buttons = [ 17 ["7", "8", "9", "/"], 18 ["4", "5", "6", "*"], 19 ["1", "2", "3", "-"], 20 [".", "0", "C", "+"], 21 ] 22 for row in buttons: 23 h_layout = BoxLayout() 24 for label in row: 25 button = Button( 26 text=label, 27 pos_hint="center_x": 0.5, "center_y": 0.5>, 28 ) 29 button.bind(on_press=self.on_button_press) 30 h_layout.add_widget(button) 31 main_layout.add_widget(h_layout) 32 33 equals_button = Button( 34 text="=", pos_hint="center_x": 0.5, "center_y": 0.5> 35 ) 36 equals_button.bind(on_press=self.on_solution) 37 main_layout.add_widget(equals_button) 38 39 return main_layout Here’s how your calculator code works:

The next step is to create the .on_button_press() event handler. Here’s what that code looks like:

41def on_button_press(self, instance): 42 current = self.solution.text 43 button_text = instance.text 44 45 if button_text == "C": 46 # Clear the solution widget 47 self.solution.text = "" 48 else: 49 if current and ( 50 self.last_was_operator and button_text in self.operators): 51 # Don't add two operators right after each other 52 return 53 elif current == "" and button_text in self.operators: 54 # First character cannot be an operator 55 return 56 else: 57 new_text = current + button_text 58 self.solution.text = new_text 59 self.last_button = button_text 60 self.last_was_operator = self.last_button in self.operators Most of the widgets in your application will call .on_button_press() . Here’s how it works:

The last bit of code to write is .on_solution() :

62def on_solution(self, instance): 63 text = self.solution.text 64 if text: 65 solution = str(eval(self.solution.text)) 66 self.solution.text = solution Once again, you grab the current text from solution and use Python’s built-in eval() to execute it. If the user created a formula like 1+2 , then eval() will run your code and return the result. Finally, you set the result as the new value for the solution widget.

Note: eval() is somewhat dangerous because it can run arbitrary code. Most developers avoid using it because of that fact. However, since you’re only allowing integers, operators, and the period as input to eval() , it’s safe to use in this context.

When you run this code, your application will look like this on a desktop computer:

To see the full code for this example, expand the code block below.

Complete Code Example Show/Hide

Here’s the full code for the calculator:

from kivy.app import App from kivy.uix.boxlayout import BoxLayout from kivy.uix.button import Button from kivy.uix.textinput import TextInput class MainApp(App): def build(self): self.operators = ["/", "*", "+", "-"] self.last_was_operator = None self.last_button = None main_layout = BoxLayout(orientation="vertical") self.solution = TextInput( multiline=False, readonly=True, halign="right", font_size=55 ) main_layout.add_widget(self.solution) buttons = [ ["7", "8", "9", "/"], ["4", "5", "6", "*"], ["1", "2", "3", "-"], [".", "0", "C", "+"], ] for row in buttons: h_layout = BoxLayout() for label in row: button = Button( text=label, pos_hint="center_x": 0.5, "center_y": 0.5>, ) button.bind(on_press=self.on_button_press) h_layout.add_widget(button) main_layout.add_widget(h_layout) equals_button = Button( text="=", pos_hint="center_x": 0.5, "center_y": 0.5> ) equals_button.bind(on_press=self.on_solution) main_layout.add_widget(equals_button) return main_layout def on_button_press(self, instance): current = self.solution.text button_text = instance.text if button_text == "C": # Clear the solution widget self.solution.text = "" else: if current and ( self.last_was_operator and button_text in self.operators): # Don't add two operators right after each other return elif current == "" and button_text in self.operators: # First character cannot be an operator return else: new_text = current + button_text self.solution.text = new_text self.last_button = button_text self.last_was_operator = self.last_button in self.operators def on_solution(self, instance): text = self.solution.text if text: solution = str(eval(self.solution.text)) self.solution.text = solution if __name__ == "__main__": app = MainApp() app.run() It’s time to deploy your application!

Now that you’ve finished the code for your application, you can share it with others. One great way to do that is to turn your code into an application that can run on your Android phone. To accomplish this, first you’ll need to install a package called buildozer with pip :

$ pip install buildozer Then, create a new folder and navigate to it in your terminal. Once you’re there, you’ll need to run the following command:

$ buildozer init This will create a buildozer.spec file that you’ll use to configure your build. For this example, you can edit the first few lines of the spec file as follows:

[app] # (str) Title of your application title = KvCalc # (str) Package name package.name = kvcalc # (str) Package domain (needed for android/ios packaging) package.domain = org.kvcalc Feel free to browse the rest of the file to see what else you can change.

At this point, you’re almost ready to build your application, but first, you’ll want to install the dependencies for buildozer . Once those are installed, copy your calculator application into your new folder and rename it to main.py . This is required by buildozer . If you don’t have the file named correctly, then the build will fail.

Now you can run the following command:

$ buildozer -v android debug The build step takes a long time! On my machine, it took 15 to 20 minutes. Depending on your hardware, it may take even longer, so feel free to grab a cup of coffee or go for a run while you wait. Buildozer will download whatever Android SDK pieces it needs during the build process. If everything goes according to plan, then you’ll have a file named something like kvcalc-0.1-debug.apk in your bin folder.

The next step is to connect your Android phone to your computer and copy the apk file to it. Then you can open the file browser on your phone and click on the apk file. Android should ask you if you’d like to install the application. You may see a warning since the app was downloaded from outside Google Play, but you should still be able to install it.

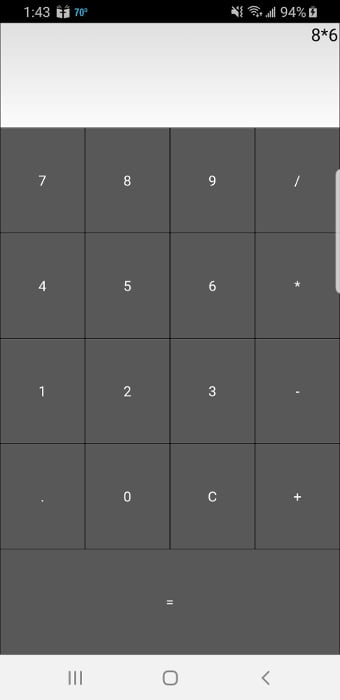

Here’s the calculator running on my Samsung S9:

The buildozer tool has several other commands you can use. Check out the documentation to see what else you can do.

You can also package the app using python-for-android if you need more fine-grained control. You won’t cover this here, but if you’re interested, check out the project’s quickstart.

The instructions for building an application for iOS are a bit more complex than Android. For the most up-to-date information, you should always use Kivy’s official packaging documentation. You’ll need to run the following commands before you can package your application for iOS on your Mac:

$ brew install autoconf automake libtool pkg-config $ brew link libtool $ sudo easy_install pip $ sudo pip install Cython==0.29.10 Once those are all installed successfully, you’ll need to compile the distribution using the following commands:

$ git clone git://github.com/kivy/kivy-ios $ cd kivy-ios $ ./toolchain.py build python3 kivy If you get an error that says iphonesimulator can’t be found, then see this StackOverflow answer for ways to solve that issue. Then try running the above commands again.

If you run into SSL errors, then you probably don’t have Python’s OpenSSL setup. This command should fix that:

$ cd /Applications/Python\ 3.7/ $ ./Install\ Certificates.command Now go back and try running the toolchain command again.

Once you’ve run all the previous commands successfully, you can create your Xcode project using the toolchain script. Your main application’s entry point must be named main.py before you create the Xcode project. Here is the command you’ll run:

./toolchain.py create

There should be a directory named title with your Xcode project in it. Now you can open that project in Xcode and work on it from there. Note that if you want to submit your application to the App Store, then you’ll have to create a developer account at developer.apple.com and pay their yearly fee.

You can package your Kivy application for Windows using PyInstaller. If you’ve never used it before, then check out Using PyInstaller to Easily Distribute Python Applications.

You can install PyInstaller using pip :

$ pip install pyinstaller The following command will package your application:

$ pyinstaller main.py -w This command will create a Windows executable and several other files. The -w argument tells PyInstaller that this is a windowed application, rather than a command-line application. If you’d rather have PyInstaller create a single executable file, then you can pass in the --onefile argument in addition to -w .

You can use PyInstaller to create a Mac executable just like you did for Windows. The only requirement is that you run this command on a Mac:

$ pyinstaller main.py -w --onefile This will create a single file executable in the dist folder. The executable will be the same name as the Python file that you passed to PyInstaller. If you’d like to reduce the file size of the executable, or you’re using GStreamer in your application, then check out Kivy’s packaging page for macOS for more information.

Kivy is a really interesting GUI framework that you can use to create desktop user interfaces and mobile applications on both iOS and Android. Kivy applications will not look like the native apps on any platform. This can be an advantage if you want your application to look and feel different from the competition!

In this tutorial, you learned the basics of Kivy including how to add widgets, hook up events, lay out multiple widgets, and use the KV language. Then you created your first Kivy application and learned how to distribute it on other platforms, including mobile!

There are many widgets and concepts about Kivy that you didn’t cover here, so be sure to check out Kivy’s website for tutorials, sample applications, and much more.

To learn more about Kivy, check out these resources:

To see how you might create a desktop application with another Python GUI framework, check out How to Build a Python GUI Application With wxPython.

Mark as CompletedWatch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Build Cross-Platform GUI Apps With Kivy

Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. No spam ever. Unsubscribe any time. Curated by the Real Python team.

About Mike Driscoll

Mike has been programming in Python for over a decade and loves writing about Python!

Each tutorial at Real Python is created by a team of developers so that it meets our high quality standards. The team members who worked on this tutorial are: